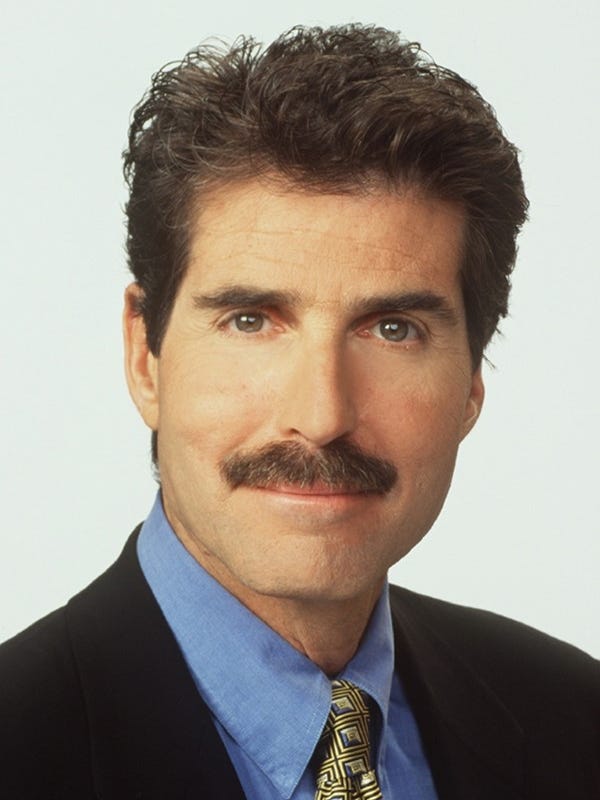

By John Stossel

Before anyone was “canceled” for saying a “wrong” thing, actress Emily Blunt and I feared speaking.

“It was terrifying … you’re just gripped with terror,” says Blunt in my new video.

I also used to wake up scared, fearing I might have to do a few seconds of live TV.

We feared speaking because we are both stutterers.

“Are you cured?” I ask Blunt.

“Are you?” she shoots back.

No, is the answer. Neither of us is cured. Stutterers rarely lose our fear of some words.

But we’ve found ways to cope.

Blunt avoids situations that trigger her stutter.

“I want to pitch a scene,” she says, “I can’t do it … I would rather say, ‘Give me the scene and I’ll write it and then I’ll send it to you.’”

On the phone, she fears trying to say her name. “If I’m calling someone and they go, ‘What’s your name?’ It’s tough.”

Our stuttering was worse when we were kids. Blunt tried not to speak. She just shut up.

“I didn’t want to be in any of the school plays. I did not want to read out my poem in class.”

She wanted to keep her problem secret.

“You did not talk about it at all.”

Her family rarely talked about it even though her grandfather, uncle, and cousin stuttered too.

“We have to destigmatize this thing,” she tells me. “Nobody talks about it.”

That’s why she was talking to me.

Both Blunt and I work with a charity called the American Institute for Stuttering. AIS tells stutterers: go ahead and speak, even if that means stuttering in front of people.

This “go ahead and stutter” treatment is probably one of the better options. The happiest stutterers are those who speak freely, even if they stutter.

But Neither Blunt nor I want to stutter in front of people.

It really misrepresents you,” says Blunt. “You know what you want to say … but you can’t convey it. It’s just imprisoning.”

And embarrassing.

“The shame … that’s the hardest thing,” says Blunt.

And yet she’s a hugely successful actress.

Blunt doesn’t stutter when she acts. That’s not unusual. Playing another character allows many stutterers to be fluent. It why you probably don’t know that Samuel L. Jackson, Bruce Willis and James Earl Jones stutter, too. They just don’t stutter on stage.

Blunt discovered the benefit of “acting another part” when she was 12. Doing impressions, she became fluent.

“I could mess around in the playground and do silly voices,” she says.

A teacher noticed that. He encouraged her to act in a class play.

“I did a really stupid Northern English accent. It did allow for great fluency!”

Did that start her movie career?

“It would make a great sound bite, but I wouldn’t say it became the moment where I decided to be an actress. But it did free up my speech in a huge way.”

But while actors can do other voices, I couldn’t do that when I got a job as a TV reporter.

I didn’t choose that job. I fell into it, never imagining that I’d go on the air.

Seattle Magazine had offered me work in their circulation department, but the magazine closed before I got there.

“Want to work in our TV station?” a manager asked.

“OK,” said young me.

I did research for anchors and avoided speaking myself.

Then they forced me to cover a story. I’d get a film editor to cut out my blocks. I dreaded speaking.

What finally helped me was intensive therapy at a clinic in Virginia. They used computers to reward us stutterers if we initiated sounds … gently.

They also slowed our speech to two seconds per syllable. That was really tedious. We sounded like cows mooing. But it helped me. Soon I learned to speak without blocking.

It was as if a cork had been removed from my throat. You couldn’t shut me up. That treatment allowed me to have a TV career.

I assumed that treatment would work for everyone, but it didn’t. Maybe other stutterers, less motivated than I, didn’t spend as much time practicing. In any case, that company is now out of business.

“I don’t think one method will work for everyone,” says Blunt.

It won’t.

It’s good that we have choices.

More information about that here: www.StutteringHelp.org