A new powerful new documentary called “The Streets Were My Father” features three Chicago men, two Hispanics and one Black, who grew up without fathers. All three did hard time for serious offenses, including murder.

The film, with no narrator, just lets the men talk. None blames “systemic racism.” All concede they made bad choices, but choices nonetheless. All talked about the pain they felt growing up without a father figure to instruct, scold, guide, motivate and instill confidence and direction. I highly recommend it.

In Barack Obama’s first book, “Dreams From My Father,” he talked about the hole in his soul, having last seen his father, briefly, when Obama was 10: “There was only one problem: my father was missing. He had left paradise (Hawaii), and nothing that my mother or grandparents told me could obviate that single, unassailable fact. Their stories didn’t tell me why he had left. They couldn’t describe what it might have been like had he stayed.”

My brothers and I were fortunate. We grew up with two strong, hardworking parents, both born in the Jim Crow South. But when I grow up, most kids came from two-parent households. My father, on the other hand, never knew his biological father. A man named Elder was in his life longer than most of his mother’s boyfriends. He was an alcoholic, who routinely beat my father’s mother and would beat my father when he tried to intervene. Dad’s illiterate mother sided with her boyfriend during a quarrel with my dad and threw him out of the house at the age of 13. He never returned. This was in Athens, Georgia, deep in the Jim Crow South, at the beginning of the Great Depression.

He took a series of menial jobs before becoming a Pullman porter for the railroads. As a porter, he traveled all over the country and was amazed when he traveled to California, where he eventually relocated, and could actually walk in the front door of a restaurant and get served. My father joined the Marines, did duty in Guam during World War II and became a staff sergeant in charge of making sure the “colored” troops were fed. When he returned, he sought a job as a cook but was told, “We don’t hire (N-word)s.” So, he worked two jobs as a janitor and cooked for a white family on the weekends. After a grueling day of work, he attended night school two or three times each week to get his GED. He took courses on restaurant management and then started a small cafe when he was 47 years old, an ancient age for a first-time entrepreneur. The cafe was successful. He owned the property and bought some rental property before retiring in his early 80s.

He tolerated no excuses and always gave my brothers and me the following advice: “Hard work wins. You get out of life what you put into it. You cannot control the outcome, but you are 100% in control of the effort. Before you complain about what somebody said or did to you, go to the nearest mirror and ask yourself, ‘What could I have done to change the outcome?’ And, no matter how hard you work, how good you are, bad things will happen. How you respond to those bad things will tell your mother and me if we raised a man.”

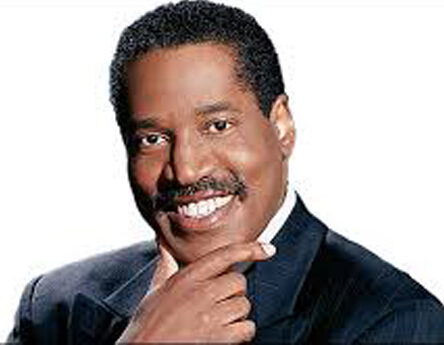

I wrote a book about the eight-hour conversation I had with this crusty old Marine, whose old-school discipline my brothers and I did not appreciate at the time. The hardback is called “Dear Father, Dear Son,” and the paperback is called “A Lot Like Me.”

Several readers who, like my dad, grew up without a father wrote to me and said that the book “changed their lives.” Many readers who, like my brothers and me, grew up with tough Depression-era World War II dads said the book changed how they saw their fathers.

Fathers matter.